Click here to play the audio version

ADDICTION SCIENCE

Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome, or PAWS, was first researched by George Koob, MD of the Scripps Research Institute in the late 1970’s and early 80’s. Prior to his work, the understanding of why an alcoholic would continue to drink would be due to alleviating active withdrawal. This led to another (flawed) assumption that treatment of alcoholism through detox would reset that alcoholic to baseline. Therefore, he or she would now have to either choose to drink or maintain sobriety. This model did not fully explain the persistent relapses and difficult time an alcoholic would face in early recovery.

Koob initially referred to this phenomenon as a ‘negative state.’ He determined that it involved changes in the brain connected to the reward center as well as surrounding structures including the amygdala. The central neurotransmitters at play include corticotropin-releasing factor and dynorphin. Secondary brain structures would include those connected to memory (hippocampus), habits and routines (dorsal striatum) and decision making (prefrontal cortex). Through disruptions in the reward pathways, and ultimately adaptation involving dopamine and glutamate neurotransmitters, the addicted individual demonstrates marked impairment in the following areas:

- Mood

- Reward processing

- Decision making

- Short-term and Long-term learning

The Dysphoric Mouse

Animal research also supports the phenomenon of post-acute withdrawal syndrome. When offered alcohol administration in laboratory settings, most mice will exhibit compulsive drinking of alcohol in a fashion similar to that of humans. Research teams can then conduct studies on those mice who have become alcoholic. They will have the mouse ‘sober up’ to monitor the mouse’s nervous system. Laboratory research has found very similar things with the mice as what we see in humans going through early recovery.

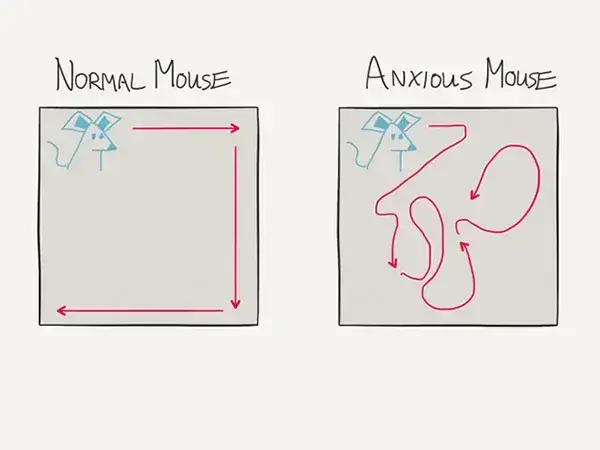

They would chart some quantitative variables such as blood pressure, pulse, food intake, and length of sleep. They also developed more qualitative means to track the anxiety and agitation of a mouse through its movement patterns.

A typical mouse in a laboratory setting will demonstrate predictable behavior. That mouse will often ‘hug the walls’ of a cage when moving during waking hours. The movement is tracked either from above or below with sensors or cameras. The agitated or anxious mouse will move in a more chaotic and disorganized fashion. The rate of walking will also increase during that state.

PAWS

Further study into this area led us to the triad of dysphoric symptoms experienced in early recovery. These symptoms are collectively called PAWS and include:

- Anxiety

- Agitation

- Insomnia

Additional ways to diagram PAWS include excitability charts, showing nervous system agitation trending downwards as time goes by. Much of the improvement occurs in the first few days, as the person is still at risk of experiencing a withdrawal seizure. This can last up to 72 hours out from the last drink. Once this is completed, the alcoholic will still experience an excited nervous system, albeit on a less intense level. The gradual return of the nervous system to a true baseline may take multiple months.

The core neurotransmitter involved during this process is glutamate. We often use specialized medications to help address these elevated glutamate levels in the brain. One example of such a medication is gabapentin. When people take this after immediate alcohol detox, they often can sleep better, feel less worked up, and are better able to engage in their therapy. This medication also shows some benefit in reducing cravings to drink.

Appreciating that PAWS exists in most people helps us hold more empathy for those individuals. At CeDAR, we work to treat the symptoms through medical and lifestyle approaches, while appreciating that the healing process takes time. Helping to support people in the very early stages allows them the opportunity to transition to more of a stable, long-term recovery.