SOCIOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

Many people still experience significant struggles in finding addiction treatment. The following comes from NIDA’s website [1] reviewing general addiction treatment statistics in America:

“According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) National Survey on Drug Use and Health [2], 23.5 million persons aged 12 or older needed treatment for an illicit drug or alcohol abuse problem in 2009 (9.3 percent of persons aged 12 or older). Of these, only 2.6 million—11.2 percent of those who needed treatment—received it at a specialty facility.”

Media in recent years has emphasized the opioid epidemic. As death from opioids continues to rise, constant attention is on the families affected by addiction. There are also many articles about public policies regarding funding sources and interventions, and general concern about the lack of available treatment.

There are many barriers to healthcare for addiction. We will begin with some discussion about three of the most common.

Lack of Availability

This applies to each level of care. There can be too few beds in a residential treatment center or not enough appointment openings for an outpatient doctor. From a public health position, the demand for addiction treatment services does not meet the supply. Historically rich areas in mental health care have the highest density of specialists (i.e. New York). Some of the most desperate states for the opioid crisis in this country have few to no clinicians (South Dakota has one addiction psychiatrist). We are assuming that all board-certified addiction psychiatrists are licensed to prescribe Buprenorphine. The density of those physicians also serves as a marker for MAT access per state.

Insurance Coverage Issues

Insurance reimbursement for addiction care is a complex issue and represents the fusion of political conflict, economic measures, and public health. Parody law requires treatment for addiction conditions be with the same degree of insurance coverage as all other general health problems. One of the ongoing concerns about insurance coverage for recovery treatment is mismatches in levels of care. Many insurance carriers do not actually use the ASAM criteria in determining health needs for different forms of treatment. They have independent criteria to determine medical necessity for such avenues as residential care or medical detoxification. They also tend to emphasize intensive outpatient services and philosophies of ‘failed lower attempts at treatment’ before deciding to authorize higher levels of care.

As you could probably imagine, the notion of requiring people to fail less intensive care poses significant risks for mortality. Especially with opioid addiction, ‘failed care’ can mean the death of someone. The controversy regarding these issues is quite extensive. It’s led to significant emotional hardship and frustration for families seeking to help the addicted.

Insurance Standards vs Clinical Standards

In contrast to some of the advanced addiction literature, there seems to be a considerable push by insurance carriers to move people to less structured environments as quickly as possible. This plays out often in the residential treatment world where a person may have reached stable medical detoxification after 3-5 days of 24/7 care and becomes unauthorized to continue at that residential level, even if the total program designed for the person were a 30-day or more path. The insurance company will cite that continued 24/7 support in classical rehab is not medically necessary, despite clinical evidence that more structured time people positively correlates with maintaining sobriety in the future.

The discussion regarding conflictual insurance reimbursement doesn’t matter for the high volumes of uninsured people in this country. For those people, much of the care tends to be emergency services. These are semi-outpatient detoxification (which has questionable efficacy) and triage to self-help groups such as Narcotics Anonymous. Fortunately, those addicted to opioids with access to buprenorphine MAT options can actually fair as well. People entering high-end residential treatments report clean urine screens from opioids and treatment retention. There is a debate about the social and psychological rehabilitation. These issues may need to be met via outpatient channels.

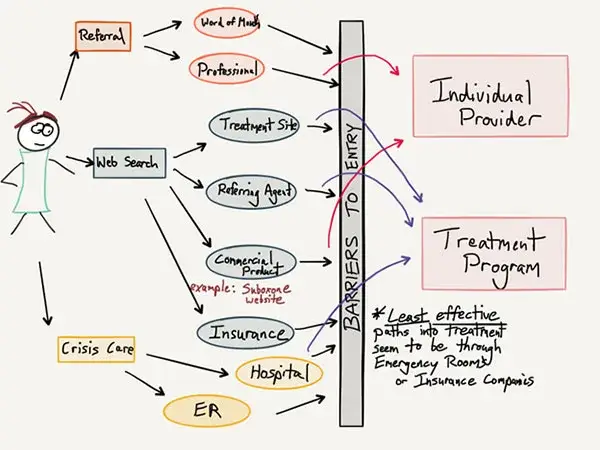

Narrow Referral Linkages

More recent issues with the opioid epidemic and the treatment industry have included in-bred approaches to addiction care, biased referrals with significant kick-backs for getting someone into rehab, and revolving door practices. Some of this connects to the pure abstinence approach of many addiction treatment centers. As you could probably guess, rejection of MAT options for care is common in the treatment world, but this seems to be changing towards multi-faceted approaches, especially with such a lethal disease on our hands.

Lack of scientific rigor in the industry has promoted primarily 12-step referrals for people following 30-day residential stays. This practice stems from the historical links between residential care facilities and peer support programs. Beginning in the 1950s in St. Paul, Minnesota, the practice of inviting AA groups into the addiction sanitariums was useful and cost-effective. This classical residential treatment program is the “Minnesota Model”, named as a testament to these practices. While very beneficial to those people who followed through with meeting attendance following rehab, the attrition rate was overall too high. When combined with opioid tolerance and amplified cravings approaching discharge, the mortality rate for opioid addicts is actually 3-4 times baseline upon checking out of rehab.

Biased Treatment Plans

Ironically, treatment itself actually had the ability to be a barrier to treatment. Many people in residential care would receive referrals to continued residential care or outpatient programs with similar philosophies as the rehab. People who questioned the fit of the clinical model for their case were ‘treatment-resistant’ or ‘not yet ready to quit’ drugs and alcohol. By offering narrow ranges of referrals, people would often graduate rehab without any aftercare plan for longitudinal care

This phenomenon is also true from the opposite side. Many physicians and staunch promoters of MAT have a minimal drive to refer people to peer support programs or therapy avenues. Prior experience, or vicarious experience from previous people, can lead those physicians to undervalue the role of 12-step or comparable programs as part of a complete recovery package. Those people will then get under-referred to available options.

[1] Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institutes of Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

[2] NSDUH (formerly known as the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse) is an annual survey of Americans aged 12 and older conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services.

Read more CeDAR Education Articles about Sociology and Public Health including Social Cost of Opioid Painkiller Abuse.