FAMILY RECOVERY

No other health field discusses motivation to the same degree as addiction treatment. So much of our clinical work is appraising people’s motivation to change. We adapt our treatment plans in accordance with this motivation (or lack thereof). In some ways, building a strong motivation for recovery sets the stage for any treatment that may follow. There is an evidence-based form of therapy used for this topic called “Motivational Interviewing.” It was designed by William Miller and Stephen Rollnick in 1983. Motivational interviewing skills help experienced clinicians continue supportive dialogue with your family member where your efforts may have broken down. This session will help you build some of the same skills.

Sometimes I joke with my colleagues that motivational interviewing may help us clinicians just as much as our clients. It gives us emboldened patience to deal with such a chronic disease!

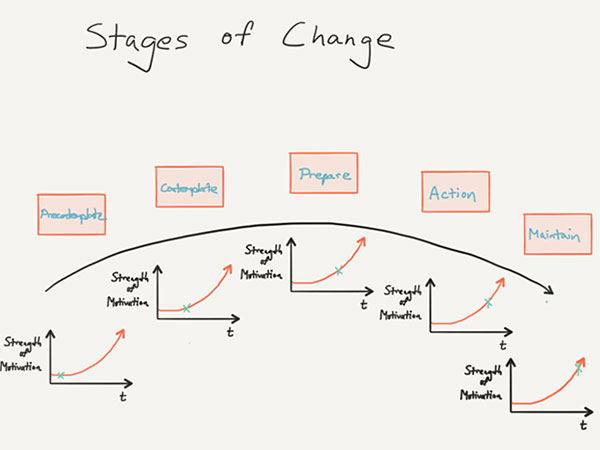

For any change process in health, we diagram 5 primary zones that a patient could be in. These stages are as follows:

- Precontemplative

- Contemplative

- Preparation

- Action

- Maintenance

To foster any progress in motivation, it is important to have some sense of where your family member may be at this stage of change continuum. Clinical efforts appropriate for someone in an active stage of change would be often wasted on someone who is in a precontemplative stage. Try to gauge where your family member is at present day (it can actually be worthwhile talking to them directly about it if you feel they’re open to a dialogue).

Core Assumptions

There are some important assumptions we make when embarking on any therapy initiative in which motivation will be key. These assumptions are as follows:

- The true motivation to change MUST come from the patient

- That patient is ambivalent (internally torn) about changing substance use

- We as clinicians are biased towards quitting substances rather than neutral (“Yes, I really do want you to quit heroin”)

- Change takes time

As we apply item number 1 above, much of the process of motivational interviewing is through identifying ‘change talk’ rather than ‘resistance talk.’ This change talk could sound like:

- “I can’t keep doing this stuff!”

- “What resources do you have to help someone with my addiction?”

- “I know this behavior isn’t good for me.”

The art of this form of therapy is to keep the patient talking about these things. Once the clinician is the primary speaker and the patient is really just listening, the arc of change may be slowing down or outright stopping. These same concepts apply to you, a family member. Through getting your family member to ‘say more’ and keep the dialogue going about alcohol or drug use, there is room for that person to identify drives for change.

Does your loved one need rehab?

Four Principles of Motivational Interviewing

- Express empathy about the suffering from the addiction and difficulty to change

- Develop goal discrepancies

- Roll with resistance

- Support self-efficacy

Express Empathy

If you experience minimal empathy in your family member’s struggle, I would recommend exploring some of our other tracks through RecoveryArc. The inherent suffering from an addiction is profound and can lead to the person becoming more discouraged. Through empathy and acknowledging the difficulty in changing, your family member will feel less attacked and less judged. This allows him or her to express emotional pain and legitimately search for support of a change process. If he or she only really knows criticism around addiction, opening up to other supportive figures may be more difficult.

Another way of saying this is that through judgment and criticism of your family member’s substance use, you will surely lose them from the dialogue. No dialogue, no ability to support.

Develop Goal Discrepancies

This set of tactics involves challenging your family member and improving what is called ‘reality testing.’ Reality testing is present when people are authentic, aware, and accepting of the truth of any given situation. The opposite of reality testing is cognitive distortions.

As an example to better describe this, I have worked with numerous people who thought they could control their drinking amidst early signs of cirrhosis of the liver. The reality testing of this person is quite poor and may need to be challenged in a kind but firm manner.

Goal discrepancy topics may include financial costs from addiction, relational issues, goals of reconnecting with children, or general health topics. The clinician’s job in this area is to help further the change talk in regards to substances versus something else in the person’s life. Because of the nature of addiction, the substance use tends to overwhelm things and lead to the general neglect of other life areas.

Roll with Resistance

Much of motivational interviewing is based on this principle. People will often respond negatively to forces outside of their control, hence objecting to someone who may be resisting change seldom goes well. In fact, it may bolster further talk on the other side of change (remember there is ambivalence present). For family members, this essentially means don’t argue or get into an outright conflict about the addiction. Conflict will raise up the addicted member’s defense mechanisms and the dialogue will suffer or completely stop. We will discuss professional interventions in a later session, but even those efforts (which do become conflictual at times) understand the inherent ambivalence present with the patient and the use of effective motivational strategy to foster change.

Support Self-Efficacy

Small strides are meaningful and should be acknowledged. Even if the going is slow, it can be worthwhile to validate change efforts made by your family member. Examples of this could involve simply using the word ‘alcoholic’ when discussing drinking patterns or being open to learning more about treatment options. This principle is especially important if your family member is making efforts to abstain from alcohol or drugs. We would view even a few days without drinking as a success even if that person went back to drinking afterward.

This principle acknowledges that people often have poor confidence that they could succeed in quitting substances. By bolstering their efforts, we help to build greater confidence and improve recovery rates. There is a large body of clinical evidence supporting this notion ranging from tobacco quit rates to weight-loss.

By understanding these principles of motivational interviewing, you can actually use some of the same tactics as addiction treatment professionals. All of these are sensible and appreciate the fact that change takes time, the fundamental desire for change must come from the addicted person, and that people are internally conflicted about substance use. Healthy families are able to respond appropriately to the cues given by the addicted person. If your family member is open to a dialogue about substance use, be a good listener for change talk. If that person shuts down but acknowledges a willingness to talk it through with someone other than family, be open to respecting those boundaries.